Wyrd Designs: Understanding the Words – Asatru

October 22, 2010 by K. C. Hulsman

0

tweets

retweet ShareA factoid that not many outside of the Asatru faith realize is that the term Asatru is entirely a recent invention. The ancient followers and believers of the old Gods of Germany, Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxon England did not have a name that they called their religion because their religious identity was simply part of their cultural identity. It wasn’t until Christianity encroached on these ancient polytheistic cultures that the term Heathen (used by the 4th Century Christian Goth Ulfilas in his translation of the Bible) was first employed to distinguish between Christians and the ‘other’. It is believed that Ulfilas was inspired to follow the example the Romans had created when they termed the word pagan. Ulfilas’ use of the term heathen in his translation of the Bible would trickle down the centuries until the word was used in various sagas later.

Through the centuries since, the terms pagan and heathen have in the common vernacular become somewhat interchangeable, and the meaning has shifted and changed. Christians later used the term to describe any non-Christian people regardless of geographic location, and eventually the word was stripped of even religious connotation in some usages to merely refer to something that is strange or uncivilized. As such while there is a movement of some modern-day practitioners trying to reclaim the original definition of the term Heathen and using it to name their collective religious identity as Heathenry, many others have opted instead with finding other words and terms.

Among these we find the term Asatru derived from the 19th Century created term Asetro, used by Edvard Grieg in his 1870 opera Olaf Trygvasion. The term etymologically is meant to be a contraction between the root word for the ‘Aesir’ (Gods like Odin, Frigga, Thor, etc.) and the root word for ‘faith’, and thus can be understood to mean something like the ‘Aesir’s Faith’, or ‘Those True in the Aesir (Gods).’ While the term may have been coined over 140 years ago, it doesn’t appear to have come into use as a term describing a current religious identity until sometime after the modern-day reconstructionist movement started in the 1970’s. Since Asatru is a word based on Old Norse terms, if one applied Old Norse grammar usages then the term ‘Asatru’ is the plural name for the group, and the name for an individual practitioner should be ‘Asatruar.’ However, since most Americans don’t speak Old Norse, many tend to use Asatru as the term to both represent the religion overall as well as the name for an individual practitioner who follows those beliefs.

In addition to the term Asatru, we have other words that crop up as terms for this religious identity. Many European practitioners prefer to use Forn Sidr/Fyrnsidu/Forn Sed which translates to ‘old custom’. Beginning in the 19th Century the term Odinism was introduced, referring most obviously to the All-father patriarch of the Aesir: Odin. Therefore Odinism refers to those who worship Odin (and by extension the other Gods in the pantheon). While people who were Odinists have worshipped for over a century at least under that name, usually the form of religious practice is different than what you’d find amongst the reconstructionists which didn’t appear on the scene until late in the 20th Century. However… just as the terms pagan and heathen became synonyms for one another, so did the terms Odinism and Asatru, and now it very much depends who you ask on the defined nuances of practice.

More recently we also see other terms used to describe the religious faith and identity of those who honor the Aesir: the Germanic Paganism, Norse Paganism, Anglo-Saxon Paganism, and the Northern Tradition also used. There even exist a few specialized denominations (for lack of a better term) like the Vanatru (who focus their worship on the Vanic deities such as Freyr, Freyja, Nord, etc.). Some may also view Theodism as another denomination that focuses on a very reconstructionist-based, historical, geo-specific culture (like the Frisians, the Miercingans, the Normani, the Franks, etc.) as the foundation for their modern practice.

There is no one great consensus on how we are called, which is a matter that can confuse many. Just as there is also no one vast consensus on exactly how we worship and live the faith today. For some this is a point of great contention, and others see it as par for the course. Afterall, if we look to the more mainstream religions we see vast plurality of multifaceted interpretations and beliefs even within the same base ‘umbrella’ – just think of how many denominations of Christianity that exist for an example.

In the future you can look forward to more explorations into some of the words and terms used within the Northern Tradition umbrella. If anyone has specific words they’re curious about understanding better, leave a comment below please with the ‘word’ in question. In the meantime you may enjoy reading up on some of the symbols used by practitioners of Asatru, and their meanings.

Understanding the Symbols:

Part 1 – The Valknut

0

tweets

retweet ShareEvery religion and culture has an iconography which is uniquely it’s own, and the Northern Tradition is no different. Common symbols found in conjunction with this religion are the Valknut, the Mjollnir, the irminsmul, various runes, the unfortunately misappropriated swastiska, etc. But what do they mean?

The Valknut, is one of the most traditional symbols associated with the Norse God Odin. Since ancient times this symbol has been used throughout Europe in association with the God known as the All-Father, the God of Poetry, the God of Warriors, a God of the Dead, the God of Magic and Runes, the God of Wisdom, a God of Ecstasy, etc. Similar symbols were used on cremation urns by the Anglo-Saxons, or found on memorial or rune stones like the Tängelgarda Stone and Stora Hammer stones found in Gotland, Sweden as well as found among the artifacts at the Oseberg Ship burial find in Norway.

The term valknut is a modern invention, deriving from the combination of two Old Norse words: ‘valr’ (slain warriors) and ‘knut’ (knot). There are two kinds of valknuts, the unicursal, which is one continuous ribbon knotted upon itself, and the triple version which is made by entwining three separate triangles.

The valknut is used today as a symbol first and foremost of Odinic worship by those who honor the Norse God Odin, and also as a symbol for those who honor the Aesir, the ancient Gods of the Germanic & Scandinavian peoples, such as Heathens, Germanic Pagans, Northern Tradition Pagans, Anglo-Saxon Reconstructionists, Asatru, Odinists, etc.

While we may not know exactly what this symbol represented to ancient peoples, there is no doubt that this was a symbol associated with Odin. In modern times the prevailing theories are that the cumulative sum of all three triangles’ sides (nine) represent the nine nights that Odin hung on the World Tree Yggdrasil. The World Tree, Yggdrassil, in turn connects to all nine worlds (Midgard, Musplelheim, Niflheim, Asgard, Vanaheim, Jotunheim, Swartalfheim, Alfheim, and Helheim) of this tradition’s cosmology.

Respected scholar Hilda Ellis Davidson sees the valknut as associated with Odin’s abilitily to bind and unbind. She writes in her Gods and Myths of Northern Europe: “Odin had the power to lay bonds upon the mind, so that men became helpless in battle, and he could also loosen the tensions of fear and strain by his gifts of battle-madness, intoxication, and inspiration.”

Yet others see it as a symbol of the dead, possibly of the battle-slain, and/or of those humans slained in blood sacrifice to Odin. This later possible interpretation is why some in the community say wearing or having this symbol tatood is like saying “insert spear here” as it’s essentially a big bull’s eye target painted on you for death or ill-luck, or divine attention to be brought to bear. Others in the community, see this superstition regarding the image as silly.

Others see it as being symbolically similar to both the triskele, as well as the triple horn symbol found on the Snoldelev Stone in Denmark. Whatever the original meaning of this symbol, the modern day community unmistakably recognizes it as a symbol of Odin, and via it’s connection as a symbol of our religious path as well.

Part 2 – Mjollnir

0

tweets

retweet ShareProbably one of the most popular symbols of our faith, if not the most popular symbol, is the mjollnir – Thor’s hammer. In the lore, there are many stories of Thor using the hammer in the defense of the Gods and people, killing the enemies of Asgard with his mighty hammer.

There are many runestones found in Denmark and Sweden, bearing both a depiction of mjollnir but also an inscription entreating Thor to hallow or protect. In the archaeological record, it’s one of the few symbols we do clearly see worn as pendants and necklaces by the ancient peoples. In fact during the period of conversion, it appears ancient jeweler’s were hedging their bets, there’s at least one example of the same mold holding both the ability to make crosses, as well as cast hammers. Some scholars theorize that the seeming popularity of such jewelry was in direct defiant or defensive response to he wearing of crosses by Christians during the tumultuous time of conversion. In fact the majority of such evidence of mjollnir necklace and pendants comes from lands that during the time the archaeological artifact dates to were in contention with Christianity.As such it may be possible that mjollnir’s were not worn until the ancient peoples had the ever-encroaching Christianity to contend with.

Etymologicaly, the word connects back to Icelandic verbs for crushing and grinding. In addition to this, there are two other theories with other possible connotations of meaning as well. It may root to the theorized Proto-Indo-European root word mele, which gives us the Latin maleus and the Slavic molot which mean hammer. Or it may root to the Russian word molniya and the Welsh word mellt, both words can be translated as lightning. Since Thor is associate with Thunder and lightning this connection would make as much since as the other connections from the mythological standpoint of our lore.

Today, as then, the symbol is worn by us in the Northern Tradition as a symbol not only of Thor, and a symbol that invokes Thor’s protection, but also as a symbol of our faith when we are surrounded by other faiths.

Part 3 – Irminsul

Wyrd Designs – Understanding the Symbols Part 3 – Irminsul

May 12, 2010 by K. C. Hulsman

0

tweets

retweet ShareThe Irminsul is a symbol found in antiquity, but unlike the mjollnir (Thor’s Hammer), this is not a symbol that we have any evidence of it ever being worn. Instead it appears to be a communal symbol, erected in honor of the Gods.

The Irminsul, in the Old Saxon language means mighty pillar, and it may connect to a possible god of the Saxon tribe by the name of Irmin as well. The existence of Irmin is at best a supposition and is by no means absolute. Some scholars who do accept the possibility of this god, think Irmin could potentially be Odin. Since there are theories that the Irminsul may be a symbolic representation of Yggdrasil, this theory would indeed make sense within the cosmological framework and obvious connection between Odin and Yggdrasil. Yet still other scholars propose that perhaps Irmin is an aspect of the God Tyr. Other’s look to Tacitus’ Germania and mentions of the “Pillars of Hercules” and see associations with Thor. What does Hercules have to do with anything? Well you have to understand that the Romans were fond of alikening other cultures to their own. Romans were known to sometimes identify the Germanic Thor with their Hercules. Regardless of the fact which God this symbol may have been intimately connected with or not… the fact remains it was indeed a symbol of their religion and by extent tribal identity.

Archaeological and written accounts of these mighty pillars seem to be relegated solely to Germania. In the 8th Century document, the Royal Frankish Annals, we learn that during the Saxon War campaign Charlemagne repeatedly orders the destruction of the Irminsul. Destroying it would strike a mighty blow because it was an iconic symbol of the might of their gods and the power of their culture. From the description provided in this record and taking into account modern geography, scholars believe that this holy site would be located in the Teutoburg Forest near Obermarsberg, Germany. By Church tradition, a stone pillar was dug up in this area in the 9th Century and moved to the Hildesheim Cathedral. This particular Cathedral, and others in Germany, would commemorate Charlemagne’s victory and destruction of the Irminsul during the fourth Sunday of the Catholic Lent season. Poles would be erected with a separate cone or pyramid shaped box atop them that the youths were encouraged to knock down.

In the 9th Century document, De Miraculis sancti Alexandri ,we are provided with another written account of the Irminsul where it is described as an erected wooden pillar worshipped outdoors. There are of course other accounts as well, but their relevancy and description leaves a lot to be desired.

While there’s no firm proof of such a connection, I personally believe that the tradition of the “May Pole” which is a heavily Germanic custom to begin with, is indeed connected to the Irminsul. If we look to accounts involving Thor’s Oak, the holy groves of the Gods as described in Adam of Bremen and in passing in Tacitus’ Germania it all appears to be of enough sameness to derive from the same source. While the Irminsul appears to be confined in occurrence to Germania, we do have in Norse derived sources references to God poles and nithling poles. These may be a related cousin-like custom as well, ultimately all deriving from the same source.

So what exactly does an Irminsul look like? The simple answer is we don’t know. Some think it was simply a pole, perhaps with an idol carved upon it or placed onto it. Others envision it like a ‘T’ shaped pole where the top is depicted with decorative branches. This later symbol is more commonly used by reconstructionists today based on the controversial Externsteine relief, which most scholars feel is NOT a representation of the Irminsul.

Regardless of what the Irminsul may or may not look like, symbols are ultimately what we make of them. Modern day reconstructionists when they use this symbol, tend to see it as a great universal symbol. Usually it is used to represent the coming together of those of the Northern Tradition to worship our Gods. They do tend to think of this great and mighty pillar as a representation of Yggdrasil, and therefore the symbol through which we are connected to the 9 worlds of our cosmology.

Part 4 – Sunwheels (Solar Crosses & Swastiskas)

Wyrd Designs: Understanding the Symbols Part 4 – Sunwheels (Solar Crosses & Swastikas)

May 20, 2010 by K. C. Hulsman

3

tweets

retweet12

ShareFrom ancient sources going back thousands of years, we have two types of sunwheels present in the archaeological record. The first is known as a solar cross, which is a circle bisected by a horizontal, and a vertical line arranged in the shape of a cross. The other incorporates the sowilo rune (which literally means ‘sun’) and may be known as a fylfot or swastika (which infamously was misappropriated by the Nazi party in World War II). Variations of this later type of sunwheel can incorporate a varying number of sowilo runes (two or more) into its symmetrical design.

This symbol is clearly connected to the Goddess Sunna, she whose chariot draws the sun in it’s path across the sky. Sunna (or Sol) is described in our tradition as the Goddess who in her chariot drawn by horses guides the sun in its track, as her brother Mani similarly drives the moon coursing through the sky. We have no actual depiction in the archaeological record of Sunna herself, the closest we come is the Trundholm sun chariot from the Nordic Bronze Age (1700 BCE – 500 BCE) found in Denmark, which depicts the sun (not the Goddess) being pulled by a horse drawn chariot, and the wheels of the chariot are clearly in the form of solar crosses, or sunwheels.

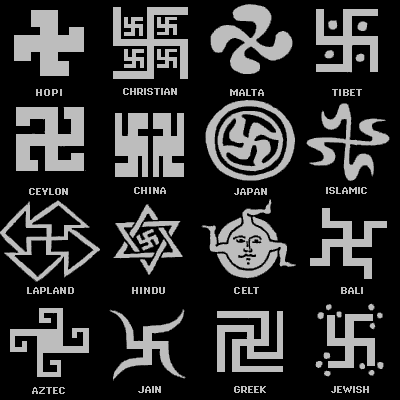

The other sunwheel, the swastika is a symbol sacred to many world religions, you’ll find it used among Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Grego-Roman architecture and jewelry, and other Asian and Indo-European cultures and religions. Depictions of the swastika appear on various sundries including jewelry, runestones, swords and spears, cremation urns, etc. Throughout Germania, Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxon finds.The symbol has even cropped up closer to home for most Americans, in that it was a sacred symbol of several Native American tribes including the Navajo, Apache, and Hopi.

The word swastsika derives from svastika a much older word from the Sanskrit language, which etymologically is comprised of words meaning both good and well-being, and thus the symbol can be interpreted to mean that it is a charm or blessing for good health. In the Germanic tradition, Sunna, is not only the Goddess that draws forth the Sun, but is linked with healing in one of the Merseburg Charms as well. Since the Northern Tradition sprung from an agriculturally focused society, they viewed the year as broken up into only two seasons: summer and winter. Winter was the time when food was scarce, when disease ran rampant and illness, malnutrition and the cold weather took lives. Summer was seen as a time of not only warmth, but a time where food was more abundantly available.

Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology describes the traditional folk practices for Midsummer celebrations in the areas where the Norse Gods were once (and in some cases still are) honored is to set a sunwheel (or a wagon wheel) on fire. In some cases the wheel was simply lit locally and incorporated into the Midsummer bonfire. In other cases people trekked out into the countryside, found a hill, set the sunwheel on fire, and let it roll down the hill as they chased after it, people watching and cheering as they watched it roll along it’s fiery way, as vegetation caught fire. Sometimes mini-fires were set in the fields, as a way of directly burning in offering the crops that the sun had helped to grow, or fragrant herbs were tossed into local bonfires instead.

It is possible, that just as Native American tribes would regularly set clearings on fire for the sake of agriculture and to lure bigger game to lush fields, that the selective burning on the fields may have also been conducted not only as an offering, but potentially to help the land so that future crops were more bountiful. As we learned after Mt. Saint Helen’s blew its top, fire is actually a healthy part of nature, as it can help fuel rapid growth and renew the land. This is why the Forestry Service has now abandoned their previous policy of total fire suppression in the fight against wildfires. Sometimes they will now let forests burn because it is healthier for the forest in the long run to do so.

While there’s no doubt both types of sunwheels, solar crosses and swastikas, connect to the Goddess Sunna, some scholars including Hilda R. Ellis Davidson theorize that the swastika may be also connected to Thor, and therefore the symbol was a representation of mjollnir. HRED supports this theory by looking to the neighboring tradition of the Finnish Sami. On the shaman drums, it wasn’t uncommon to see a depiction of a man holding either a hammer or axe, or a swastika symbol. This male figure is identified as the Lappish equivalent to Thor, their Thunder God Horagelles. Considering that the symbol is comprised of two or more sowilo runes, and side by side sowilo runes which resembled lightning bolts were used for the Nazi SS, while this connection is less direct than with Sunna, it is to my mind a viable possible connection. Although I would posit a later appearing connection with Thor, and that the symbol was always closely associated with the Sun, and therefore Sunna.

Today, while many Heathens recognize both symbols, many Heathens tend to shy away from the use of the swastika symbol and instead use the solar cross symbol. This shyness with the swastika is firmly rooted in the atrocities performed by the Nazis in World War II. Today, the swastika tends to be far more associated with hate groups. For this reason many of the Native American tribes will no longer create arts and crafts baring this symbol, the symbol is banned from use except when used in historical context in Germany and Brazil. Yet the symbol is still clearly used on both the Finnish Air Force insignia, as well as in connection with the office of the Finnish President. Of those modern Heathens who do use the symbol, many do so in the privacy of their own homes, or in subtle ways. There are some who do fully embrace the symbol trying to reclaim it and educate in the process, but they are a minority.

What do you think? Should we reclaim the swastika? Or because the mainstream culture views it as being synonymous with racism and hate should we abandon the symbol in our practice today? Do chime in with your opinions.

Part 5 – Aegishjalmr

While our religion is at its heart an agriculturally derived religion, there was without a doubt focuses on military cultuses, and aspects of military life that also comprised the pre-Christian lives of ancient Heathens. Afterall, a culture needed both food to sustain it as well as the ability to defend itself (or for some to also wage war against others).

The Helm of Awe (or The Helm of Terror) refers to an item attested to in the sagas of yesteryear. While its translated name might suggest that it’s speaking about an actual physical helm or helmet made of sturdy stuff… it doesn’t appear that the symbol originally was such. Rather that the helm of awe represented a magical charm for protection that yes, was indeed somehow connected to a head-wrapping or animal skin.

Throughout the lore there are instances of magical charms used to affect the sight. In Eyrbyggja saga, Katla (a skilled seidhkonna) casts a form of magic upon her son Odd to hide him from his pursuers. Each time the men search the house, instead of seeing him they see some other object instead. Believing a trick is at play, or that ‘they have had a goatskin waved round our heads’ they bring in another magic worker, who puts a sealskin over Katla’s head to negate her magic making Odd visible. We see this again in Reykdoela saga as well as Njals saga as well, of goatskins being wrapped around the head for magical purposes.

By the time we begin to see the helm of awe mentioned as a physical helmet in the lore and history of this evolving culture, we see it most predominantly used in Medieval European manuscripts that can be as much as 300 years later than earlier manuscripts that only speak of types of magic used to trick the sight. It is for this reason that I believe that contemporary writers of the time in conjunction with other types of Medieval Literature like various stories in the Arthurian mythos, were focusing on knightly warfare and were elaborating upon older occurences and adjusting the meaning to suit their poetic license.

In the Volsunga saga, Fafnir taunts our hero Sigurd that he has used the aegishjalmr. After Sigurd later kills both Fafnir and Reginn, among the loot he acquires the famed helm. Another 14th Century source, the Sorla þáttr also speaks of the aegishjalmr, warning that Ivar should NOT look into Hogni’s face because he wore the helm of awe.

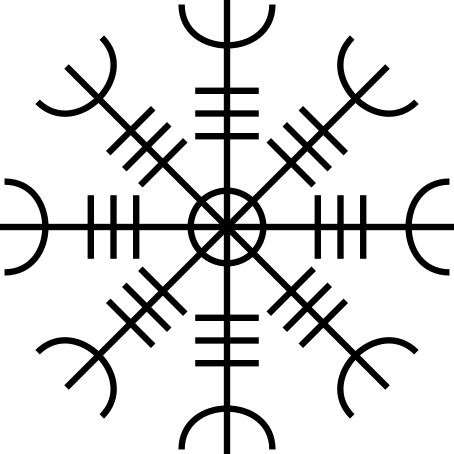

Visually the symbol is also similar to an Icelandic charm to guide a person through rough weather known as the vegvisir. In turn both of these symbols appear to potentially link back to sunwheels–I’ll cover this in a forthcoming article, so stay tuned.

At it’s core the aegishjalmr is a charm for protection, sometimes as a means to make you invisible, sometimes as a means to seemingly make you impervious to attacks, or as a terror tactic (making you seem scarier than you are). Today many heathens may opt to use this sigil as a protective charm to ward a house, or as a tattoo on their body to both represent their Asatru beliefs and for protection as well. I’ve even heard of currently serving soldiers in our armed forces, who have made the mark on the inside of their helmets.

So has anyone here opted to use it before, and if so how?

Part 6 – Vegvisir

Wyrd Designs: Understanding the Symbols Part 6 – Vegvísir

August 13, 2010 by K. C. Hulsman

1

tweet

retweet5

ShareAs is often the case, some symbols are more commonly known than others within the iconography of any religion or magical tradition, and in this regards the Northern Tradition is no different. The Vegvísir, is a magical symbol of navigation and may also be connected with actual compasses. The Vegvísir literally means in Icelandic ‘guidepost’ and is sometimes colloquially called today a Runic or Viking Compass.

Vegvísir also can be found in the late 17th century Icelandic manuscript known as the Galdrabok (it’s essentially a grimoire). Here it is a symbol of magic. We know from the manuscript that the symbol would be inscribed in blood on the forehead of the person using the charm so that they will not become lost and find their way. This is similar in nature to other symbols or magical practices we see described in the lore written at the time of the Christian conversion. The Aegishjalmr, which I’ve written on previously, is another symbol from a similar magical practice.

I’ve heard that some folks more familiar with the nuances of navigation have studied the symbol and determined that what appears to be a bunch of weird shapes and squiggles, appear to correspond to methods of navigational measurement. At least it’s quite easy to see the directional markings of N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW.

We do have two examples of a navigational Viking Sun Compass in our known archaeological record. While the items from the archaeological record don’t look like the magical symbol, somehow to me at least it still seems to be a ‘spiritual’ cousin. The archaelogical sun compass has 32 marks. The first was discovered in Greenland (1947), and the second was discovered in Poland (2000). Both date to around 1000, which is in the middle of the Viking Age (800-1300)—the time of contention and conversion between the indigenous religion and the encroaching Christianity.

Based on the seafaring accounts found in the sagas, we learn in Hrafn’s Saga that the Vikings navigated by using a ‘sunstone’. When we combine this knowledge with the actual archaeological relics… we discover an effective means of navigation. Scientists/scholars today theorize that the ‘sunstones’ mentioned in the sagas was most likely stones native to the territories of the Vikings (such as cordierite and optical calcite), which had polarizing effects. This meant that even on a cloudy or foggy day, that if they could just get a bit of a patch of clear sky at the appropriate zenith… the light would reflect through these stones when set against the compass… and show the way.

The compasses do have a margin of error and were not necessarily precise to the standards we think of today. But the Vikings most likely would have used the compass as a tool combined with other sources of information. While at this time any possible connection between the magical symbol and the actual sun compasses are tenuous at best… in a society that clearly was known as travelers who reached as far west as North America, as far east as parts of Asia, and reached into the Middle East being able to orient oneself and find the way would have been valued and important.

Famously today Icelandic songstress Bjork has the symbol tattooed on her arm. Though it’s important to note that to my knowledge the symbol is a part of her cultural heritage, and NOT used with any religious shout out to the Northern Tradition.

Today the symbol is only used by a small minority of those in the Northern Tradition, and is usually worn as a magical charm, and not used as a religiously significant symbol. Some people wear an amulet of it, have it tattooed onto them, I’ve heard of a soldier marking it on the inside of his helmet, and of someone else who cut out their own vinyl decal of it for their car.

No comments:

Post a Comment